Founding Father Benjamin Franklin famously remarked: “In this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes.” While death remains an absolute force, taxes, though difficult to escape, can be reduced. Municipal bonds issued by local and state governments, commonly referred to as tax-exempt bonds, generate tax-exempt income that is typically exempt from federal and often state taxation as well, offering domestic investors an opportunity to reduce their tax burden.

The transition to the Trump administration in early 2025 brought tax policy to the forefront, as key provisions of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) were scheduled to expire at the end of the year. Given the looming deadline, the Trump administration prioritized making these provisions permanent and ultimately succeeded with the passage of the 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). Notable provisions established by the OBBBA include making the TCJA’s reduced individual tax rates permanent, expanding the standard deduction, and preserving higher Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) exemption amounts and phaseout thresholds, the last of which maintained a significantly reduced AMT exposure for middle- and upper-middle-income taxpayers.

During OBBBA negotiations, the tax treatment of municipal bonds was a focal point of debate. Early drafts of the bill raised concerns about the longstanding federal tax exemption, including private activity bonds (a subset of municipal bonds issued to support more private projects such as airports, student loans, and infrastructure), raising the specter of the exemption being curtailed or repealed. However, the final legislation preserved the full tax-exempt status and even expanded it to include financing for spaceport infrastructure, underscoring the essential role municipal bonds play in national development. Since New York City issued the first municipal bond in 1812 to fund canal construction, the total stock of municipal debt has grown steadily, currently totaling over $4 trillion in outstanding bonds supporting the expansion of critical infrastructure and services across America, according to Federal Reserve (Fed) data.

Yet, as Benjamin Franklin proclaimed, taxes remain difficult to avoid and with the OBBBA now law, it is important to examine two areas within municipal bonds where tax consequences may still arise: the AMT and the de minimis tax rule. This paper will explore both, outlining their implications for municipal bond investors.

Alternative Minimum Tax

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) explains “Under the tax law, certain tax benefits can significantly reduce a taxpayer’s regular tax amount. The alternative minimum tax applies to taxpayers with high economic income by setting a limit on those benefits.” In other words, the AMT operates alongside the regular income tax requiring certain taxpayers to calculate their tax liability twice, once under the regular rules and once under AMT rules, with the higher calculated result being the tax liability.

To determine AMT liability, taxpayers begin with calculating regular taxable income, followed by adding back specific AMT “preference items” such as state and local tax deductions, personal exemptions, and miscellaneous business expenses. After subtracting an AMT exemption amount, the remaining income is taxed utilizing the AMT rate structure.

Below is a chart reflecting the key provisions since 2017:

While municipal bond interest generally remains exempt from federal income tax, private activity bonds are included in AMT calculations under IRS code. Complicating the issue further, if a taxpayer is not subject to AMT, they pay no tax on interest earned from these bonds. Due to the potential tax exposure, AMT bonds typically offer excess yield over non-AMT bonds.

For example, the tables below compare two State of Texas general obligation (GO) bonds. Although both carry identical AAA credit ratings and are irrevocably backed by the state’s full faith and credit, proceeds from the one on the left is utilized to fund student loans, classifying it as a private activity bond under IRS rules and therefore subject to AMT.

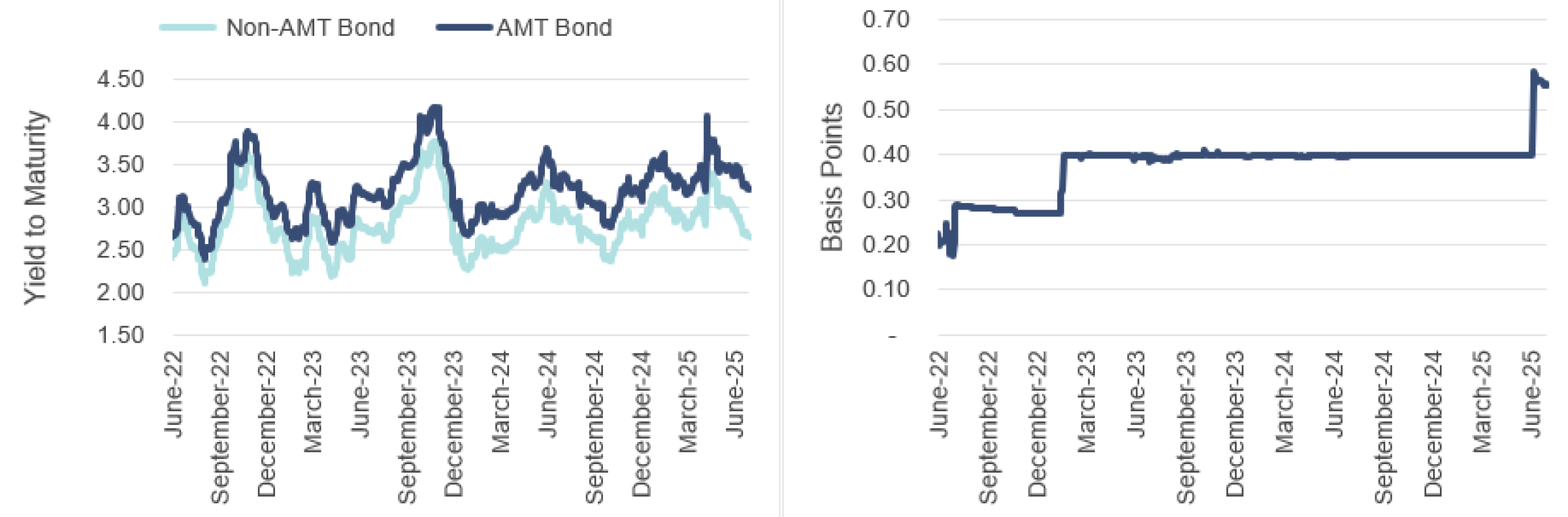

As shown in the charts below, bonds subject to AMT consistently offer additional yield compared to their non-AMT counterparts. The historical yield premium varies due to overall tax policy and market conditions. In recent years, uncertainty around tax reform coupled with elevated issuance has pushed the additional yield demanded from investors ranging between 30 and 70 basis points (bps). Yet, with tax policy uncertainty removed following the passage of OBBBA, demand improved and compressed the yield spread to the current level of approximately 55 bps.

De Minimis Tax

Merriam-Webster defines de minimis as “lacking significance or importance.” However, in the context of municipal debt, it refers to the IRS’s threshold for determining the tax treatment of bonds purchased at a market discount. The IRS considers a bond to be purchased at a market discount “if its stated redemption price at the maturity is greater than its basis after its acquisition” or more simply put, if its purchase price is lower than its redemption (maturity) value. The tax treatment of the acquired bond is determined by whether this market discount is in excess of the IRS de minimis threshold.

The IRS formula to determine the de minimis threshold is:

De Minimis Threshold = Maturity Value – (0.25% × Number of Full Years to Maturity)

As an example, a bond maturing in five years with a maturity price of $100 would be calculated using the following formula to determine what the de minimis threshold purchase price would be:

(100 – (0.25 x 5)) = 98.75

Therefore, if the bond is purchased below the de minimis threshold, or 98.75, the price appreciation up to maturity value is taxed as ordinary income, which is typically at a higher rate than capital gains.

Of course, with the IRS involved, there is often another rule to remember. De minimis tax consequences of discount bonds are not universal, but rather applicable from the perspective of every individual investor’s own experience. Therefore, if a bond is purchased above the threshold and subsequently begins trading below the threshold as market conditions evolve, the original purchase remains unaffected for tax purposes. To illustrate, consider a bond issued by the State of North Carolina in 2019 at a price of $100 with a 2% coupon.

At issuance, our example was priced at par ($100), or above the IRS de minimis threshold, meaning no additional tax consequences for original holders if held to maturity. This is illustrated in the following Bloomberg L.P. tax calculations:

Yet, beginning in 2022, the Fed pivoted to a restrictive monetary policy, prompting municipal bond yields to rise. As a result, prices adjusted lower, reflecting the upward movement in yields. As market yields rose above 2%, our example bond breached the de minimis threshold, accelerating its decline and reflecting the possible tax consequences for future buyers.

According to the Bloomberg tax calculator, (shown below), for any potential buyer at 2025 market levels the bond generates a tax liability of approximately $49k, assuming the highest federal income tax bracket.

As potential tax consequences emerge, market discount bond yields typically adjust more aggressively to higher levels than the overall market driven by less anticipated demand for the bond and degraded liquidity. As shown in the chart below, the additional yield over the London Stock Exchange Group AAA 2032 maturity curve increased from approximately 66 bps to 113 bps in June 2025.

Conclusion

We believe that municipal bonds remain a cornerstone of tax-efficient investing and offer meaningful benefits to investors seeking to reduce their tax liabilities. However, to fully realize these advantages, investor understanding of the nuances of the AMT and the IRS de minimis rule is essential for informed decision making. While passage of the 2025 OBBBA provided clarity on tax policy, the broader tax landscape remains subject to change. Therefore, investors must remain vigilant in evaluating the potential implications of these provisions on their municipal bond portfolios. By working with knowledgeable financial advisors and staying current on tax regulations, investors can continue to leverage municipal bonds effectively, navigating the complexities of the tax code to preserve the benefits of tax-exempt income.

About the Author

Michael McVicker, Executive Director, joined SCM in 1992 and has investment experience since 1992. Mike is Head of Municipal Credit Analysis and responsible for portfolio management of enhanced cash and short-intermediate municipal portfolios, as well as Associate Portfolio Manager responsibilities for the state-specific municipal bond portfolios for the Sterling Capital Funds. Prior to joining the Fixed Income team, he was SCM's Director of Operations managing the client reporting and performance team. Mike received his B.S.B.A. in Finance with a minor in Psychology from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Related Insights

01.13.2026 • Charles Wittmann, CFA®

12.11.2025 • Charles Wittmann, CFA®

12.09.2025

Gregory Zage, CFA®, Justin Nicholson

The Sterling Capital VAULT: Passive Investing is NOT Static Investing

12.09.2025 • James Kerin, CFA®